At the end of the 19th century, HG Wells imagined a

future in which industry had been completely located underground, whilst

above ground all was green and leafy.

Instead, something very different has happened to the building of structures beneath our cities...

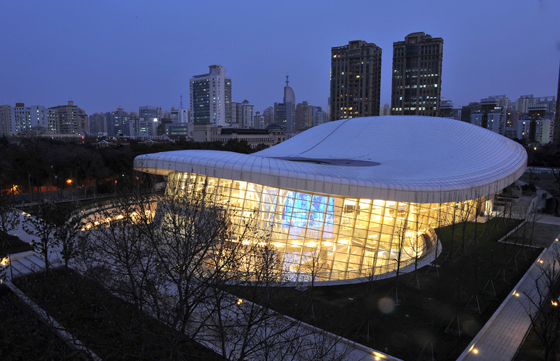

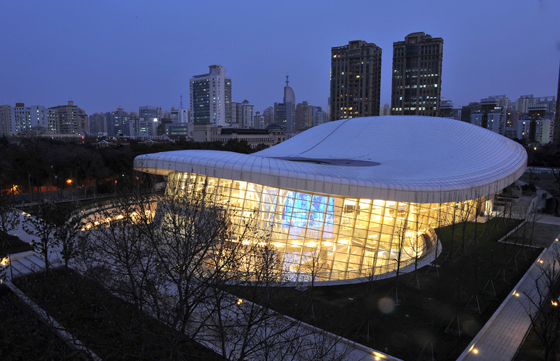

The sunlit dome of the Mansueto

library. It is immediately adjacent to the Brutalist Regenstein library

designed by Skidmore Owings Merrill and completed in 1970

In The Time Machine, HG Wells wrote: “there

is a tendency to utilize underground space for the less ornamental

purposes of civilization.” In that book, Wells imagined a future in

which industry had been completely located underground, whilst above

ground all was green and leafy. At the end of the 19th century, it was

perhaps understandable to imagine a future where this was the case.

After all, as Wells put it, referring to the working class areas of

London: “Even now, does not an East-end worker live in such artificial

conditions as practically to be cut off from the natural surface of the

earth?”

The libraries key innovation is its

subterranean automated storage and retrieval system, extending 15m

underground and which can hold 3.5million volumes

Something very different has happened to the

building of structures beneath our cities. Certainly Wells was right to

identify it as a place modern civilisation would travel to but our

cities are free of industry below ground as well as above and whilst we

still travel beneath the ground, at the beginning of the 21st century we

are also building important cultural facilities there. The phenomenon

is particularly pronounced in the USA, although it is becoming

increasingly common elsewhere. So why are we putting our theatres,

libraries and museums beneath our feet? And how are designers and

architects facilitating and making the best of this new trend?

Designed by Helmut Jahn, the Library

is effectively an above grade reading room with the book stored

beneath. The University of Chicago wanted to keep all its books on

campus

The National Law Enforcement Museum (NLEM)

in Washington DC is a case in point. Having designed a memorial to the

police forces of the United States in Judiciary Square in Washington DC,

architect Davis Buckley was charged with subsequently finding a Museum.

Wishing to create continuity with the monument, he suggested Judiciary

Square itself. Judiciary Square however, is one of the most historical

squares in the United States. Pierre L’Enfant, the original planner of

the city fought bitterly with George Washington over the laying out of

the square, with Thomas Jefferson interceding on his behalf. Abraham

Lincoln held his inaugural ball on the site. It has tremendous historic

worth.

In architectural terms there is a

strong relationship between The Museum of Law Enforcement and Law

Enforcement Memorial which sits in the square. Both are designed by

Davis Buckley architects

Furthermore Judiciary Square is lined with

important buildings and there is only really room underground. The

square is home to several specialist courts including the United States

Tax Court, the Court of Appeal for the Armed Forces and several

courthouses for the District of Columbia. In addition there are number

of important government buildings. The square, however, is being

refocused away from simply its role as the heart of the US judiciary. It

is also becoming an area of museums. The former Pension building is now

a museum of architecture called the Museum of Building. The NLEM fits

nicely into this dual role of the square.

The entrance pavilion of the Museum

of Law Enforcement is set in the historical context of Judiciary Square

in Washington DC

However there is no room for it to fit

nicely into the square! At least, above ground. Davis Buckley’s proposal

for the Museum which has just broken ground, is for two 4,000-square

foot, above-ground glass-entry pavilions. These are supposed to

symbolize the visibility of law enforcement but also provide an

unobtrusive entrance on the historic square. The visitor then descends

into the Museum, where the space will open to reveal the full expanse of

the Museum. Architecturally its not dissimilar to the 9/11 Memorial and

Museum albeit that the latter is a response to the ruins of a former

building. Still the form is similar, a glass pavilion at ground level, a

ramp down, and a vast. (Indeed the NLEM will contain a structural beam

collected from Ground Zero.)

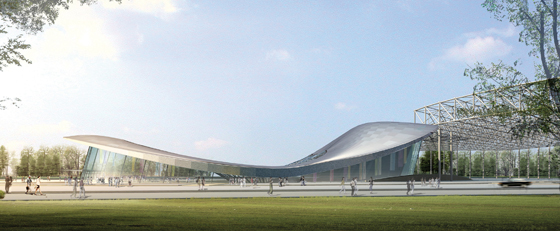

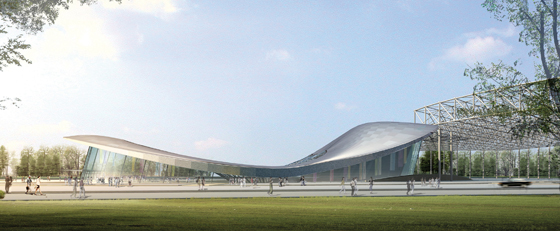

Rendering of the low slung roof of

the entrance pavilion for the Shanghai Cultural Plaza Theatre, is as

much a part of the landscaping as a separate structure

According to architect Davis Buckley he’s

had to “convince everyone from the National Capital Planning commission

to the Secretary of the Interior’ that the subterranean site was the

best place for the largest museum in the world dedicated to police. The

real reason for submerging the NLEM though is to deal with conservation

issues in a historic part of the city. As even young cities like

Washington DC age, valuable space is being found underground. They are

being made available by the architectural application of the engineering

techniques that built what Wells called ‘the less ornamental purposes

of civilisation.

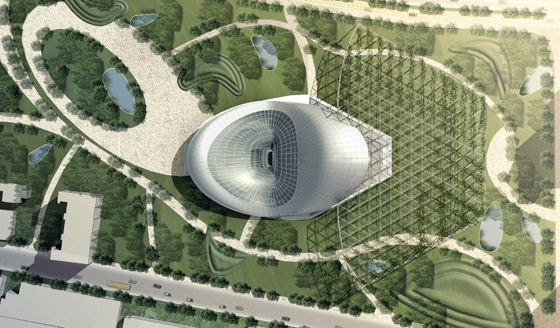

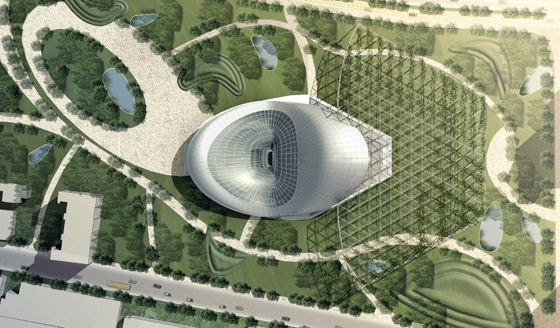

A rendering of the Shanghai Cultural

Plaza from an aerial view. The entrance pavilion for the Theatre is

part of landscape plan dominated by gentle curves

The architectural relationship between a

glass pavilion and a subterranean store or vault is the primary

relationship here. The former has a number of uses: it can provide a

means for natural light to pass into lower levels and it can advertise

the function of the subterranean structure. This is partially the case

with the Joe and Rika Mansueto Library at the University of Chicago

which is immediately adjacent to the Regenstein Library - an important

brutalist building. The domed reading room, sits modestly next to the

Skidmore Owings and Merrill building. Not only is it possible to see

what the building is for through the glass structure but conversely when

one is inside one can enjoy reading in the natural light. Beneath it a

five-storey chamber contains 3.5m books, which are retrieved and

delivered to the main desk by one of five massive cranes.

The entrance canopy is a huge

space-frame structure which will be colonised by plantlife

So in this new emerging typology we can see

an architectural relationship between a glass pavilion which advertises

the function and a lower chamber where the cultural delights are stored.

We can also see the move underground as being a means of preserving

particularly treasured architectural conservation areas - be that a

historic downtown or a more recent university campus. We can also see

that an architectural language previously reserved for metropolitan

transport - small pavilion structures both signaling to and sheltering

entrances underground have been expanded and become less incidental,

more architectural structures with the use of full glazing. Others

existing in the USA: the refurbished underground museum at Franklin

Court in Philadelphia; a new underground addition by Frank Gehry to the

Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The entrance canopy is a huge

space-frame structure which will be colonised by plantlife

It isn’t just the USA though were this

subterranean response to sensitive sites is being seen. The Shanghai

Culture Plaza is within the former French Concession on a site that

previously housed a dog-racing track, then an auditorium for political

and cultural events during Mao’s time and, latterly, a central flower

market. Its main feature is a theatre which has 570,000 sq m of its

full floor space of 650,000m sq m underground thereby making it the

largest underground theatre in the world. Although anything generally

goes in Shanghai with development, digging down was the only way to get

around high limitations in this rare conservation area in the

city.Typically for such subterranean structures a sculptural

relationship is established in the underground spaces with the entrance

above. Here it is a funnel of glass which introduces day light into

lower levels of the theatre.

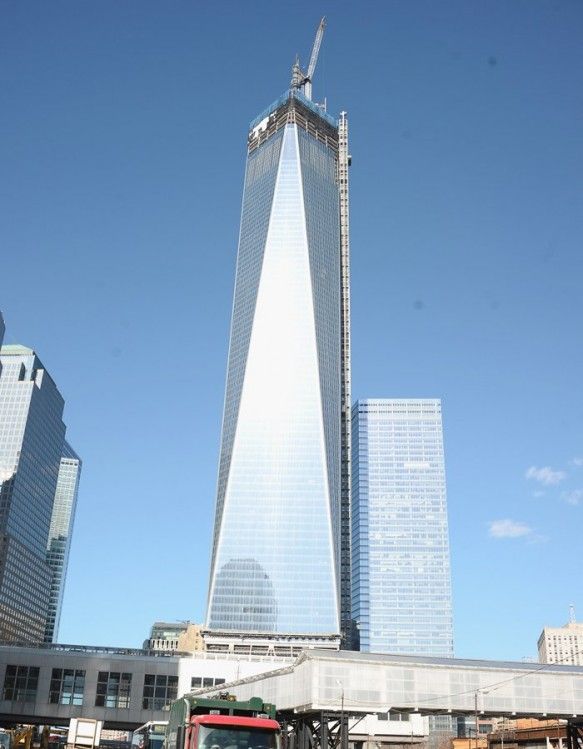

Parts of the 9/11 Memorial Museum

are artifacts themselves. The so-called ''slurry wall,'' was built to

hold back flood waters of the Hudson.

Indeed, ornament is a feature of these

expensive buildings, in contradiction to the feature of late 19th

Century life that HG Wells noted. The NLEM has a budget of $80m and the

Mansueto Library designed by Helmut Jahn, fresh from designing the Veer

Towers in Las Vegas, cost $68m to build. These cultural buildings

feature highly wrought steel forms, with full glazing in the pavilions

above and beneath crowded cities, vast amounts of circulation space - a

rare luxury in todays crowded cities. As we turn more of our cities into

conservation areas, the underground option for new cultural

institutions is becoming more and more attractive.

The west chamber which will house

some of the largest artifacts from the twin towers, including the “last

column,” removed from the site during a funereal ceremony in 2002. The

slurry wall is to the right.